Table of Contents

The Backbone of Usability in Digital Interfaces

Navigation is not a layer on top of design—it is the infrastructure. In digital interfaces, whether on the web, in mobile apps, or embedded systems, navigation is a fundamental usability mechanism that organizes content, guides actions, and ensures people can accomplish their goals without friction. Good menus makes content findable, experiences intuitive, and systems scalable. Poor navigation, by contrast, disrupts flow, increases cognitive load, and causes users to abandon tasks altogether.

Why it Matters in UX

Navigation is more than menus and buttons—it’s the system of pathways users take through information. It reflects the underlying information architecture and determines how easily people can traverse and interact with digital environments. In a landscape where attention is scarce and expectations are high, efficient navigation isn’t optional—it’s essential.

At its core, it helps:

-

Orient users to where they are within a site or application

-

Provide pathways to where they want to go

-

Reduce friction in task completion

-

Establish trust through predictability and structure

-

Expose hierarchy and content relationships through thoughtful layout

Navigation is not just usability—it is experience. Every time a user finds what they need quickly or moves from task to task without confusion, it’s because the system’s navigation has done its job well.

Information Architecture as the Foundation

Before designing any navigation interface, the underlying information architecture (IA) must be sound. IA refers to the way information is structured, organized, labeled, and related. It forms the skeleton on which navigation sits.

Key components of information architecture include:

-

Content Hierarchy: Organizing content from general to specific.

-

Taxonomies: Grouping similar items together (categories, tags).

-

Labeling Systems: Naming pages and actions in a way that is meaningful and recognizable.

-

User Flows: Understanding how users move through tasks or content.

Without a strong IA, even the most visually appealing menu system will fall short. Users will feel lost, overwhelmed, or disengaged.

Hierarchy and Visual Cues

Hierarchy in navigation helps users understand relationships between content areas. Top-level navigation might reflect major product categories or high-traffic services, while sub-menu can help users drill deeper. This visual hierarchy must mirror the mental models users bring to the experience.

Good hierarchies are:

-

Shallow when possible: Broad, shallow hierarchies reduce the number of clicks and are easier to scan.

-

Consistent: Navigation that changes from page to page or app screen to screen creates confusion.

-

Predictable: Menu positions, labels, and behaviors should not surprise users.

-

Responsive to context: Mobile hierarchies often need to collapse into drawers or accordions, while desktop versions can afford mega menus or persistent nav bars.

Visual cues such as spacing, indentation, iconography, and typography reinforce hierarchy. They allow users to scan, understand relationships, and move with confidence.

Types of Navigation Systems

Understanding the different types of navigation is critical to designing the right system for the right context. Here are some of the most common patterns:

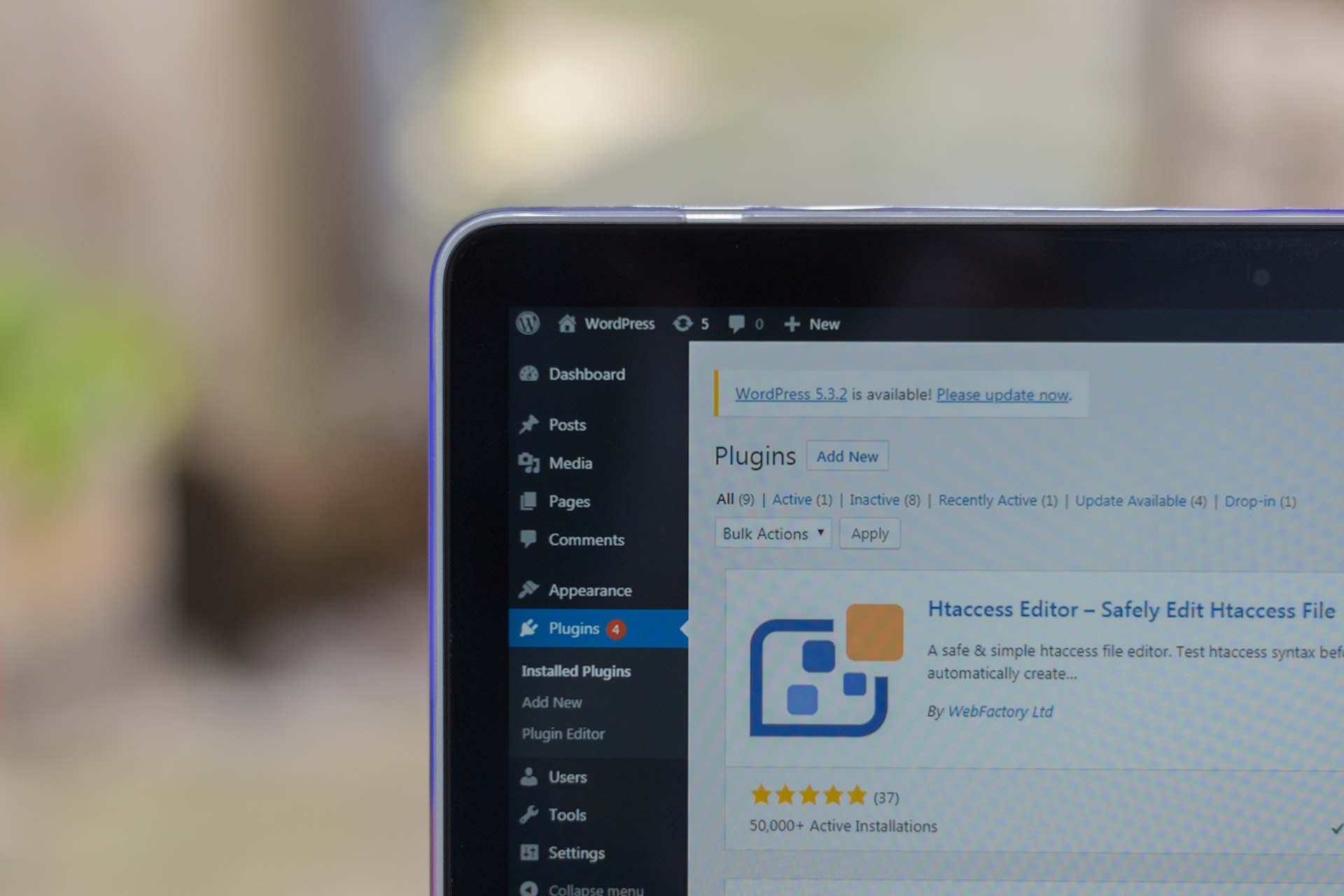

1. Global Navigation

Appears consistently across all pages. It helps users understand the major areas of a site or app.

-

Typical in websites and large applications

-

Usually horizontal (in headers) or vertical (in sidebars)

-

Often includes Home, About, Products, Services, Contact, etc.

2. Local Navigation

Used within a section of a site or app to provide access to related content.

-

Helps users explore subcategories

-

Often found in dashboards or product detail sections

3. Contextual Navigation

Appears within content to provide relevant links based on what the user is doing.

-

Common in blog articles or documentation

-

Offers related content, cross-links, and deeper dives

4. Breadcrumb Navigation

Shows the user’s current position within a hierarchy.

-

Useful for deep sites with many levels

-

Improves backtracking and orientation

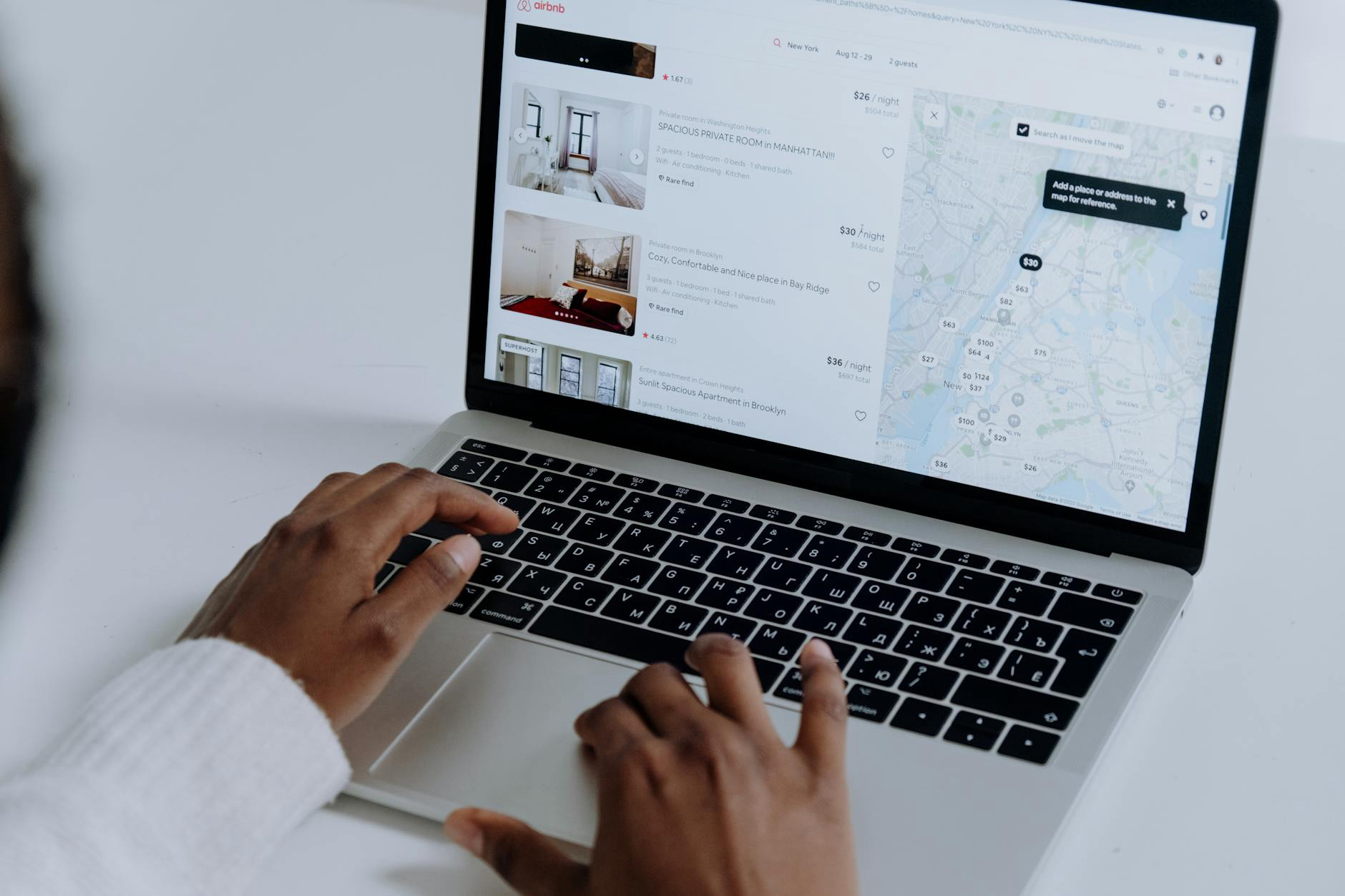

5. Faceted Navigation

Allows users to filter and sort through content dynamically.

-

Typical in eCommerce or content-heavy platforms

-

Enhances exploration without breaking page flow

6. Hamburger Menus and Drawers

Often used in mobile environments to save space.

-

Should be used sparingly on desktop, as they reduce discoverability

-

Must be clearly indicated and accessible

7. Bottom Navigation Bars

Standard in mobile apps for key actions.

-

Ideal for quick access to 3–5 core features

-

Always visible and ergonomically placed

Navigation Best Practices

Use Recognizable Patterns

Users don’t want to learn how to navigate. They want familiar patterns that work. This doesn’t mean stifling creativity—it means anchoring creativity in usability.

-

Keep the logo top-left (or top-center on mobile)

-

Place search functionality where users expect it

-

Use standard icons for carts, profiles, or menus

Prioritize Accessibility

Navigation must be inclusive. This means screen reader compatibility, keyboard support, proper ARIA roles, and contrast-aware visuals.

-

All elements should be tab-navigable

-

Menus should announce themselves and expand/collapse correctly

-

Labels should describe function, not just form (“Search” vs. a magnifying glass icon alone)

Support Multiple Pathways

Not every user follows the same path. Some search. Some browse. Some jump via links.

-

Offer redundant paths to core actions or information

-

Ensure both top-down (hierarchical) and associative (tag-based) navigation is supported

Make It Scannable

Users don’t read interfaces—they scan. Keep labels short. Group items logically. Use icons to support, not replace, text.

-

Avoid jargon or internal language

-

Start menu labels with keywords (e.g., “Pricing Plans” vs. “Our Pricing”)

Provide Feedback and State

Users need to know where they are and what they just clicked.

-

Highlight the current page or tab

-

Use animations sparingly to indicate changes

-

Ensure back buttons work predictably

Navigation and User Journeys

Navigation doesn’t exist in isolation. It must reflect and support the user journey. To design effective navigation, map out:

-

Entry points (homepages, search, marketing pages)

-

Core tasks (purchasing, subscribing, downloading)

-

Exit paths (checkouts, form submissions)

-

Recovery flows (errors, backtracking)

When navigation anticipates user goals and adapts to different journey stages, it becomes an enabler of success, not a barrier.

SEO and Navigation

Navigation influences not only usability but also how search engines crawl and understand your site. A clear navigation system:

-

Encourages deep indexing

-

Distributes link equity across key pages

-

Informs structured data and site maps

Best practices for SEO-friendly navigation include:

-

Using clean HTML structures (unordered lists, semantic nav tags)

-

Avoiding excessive JavaScript dependency

-

Ensuring all core content is reachable within three clicks

-

Using descriptive anchor text

Navigation and findability are deeply intertwined. If users or bots can’t find your content, it may as well not exist.

Adaptive and Personalized Navigation

As systems grow more intelligent, navigation can adapt based on user roles, behavior, or preferences.

-

Role-based navigation is common in SaaS applications where admins see more options than end users.

-

Behavior-based personalization can reorder items or highlight actions based on past activity.

-

Context-aware navigation adapts to device, location, or time—for instance, showing contact info at night or surfacing recently viewed items.

The challenge is keeping personalized navigation usable and predictable. Transparency is key. Users must know why something is being suggested or shown differently.

Navigation for Complex Systems

Enterprise applications, large-scale eCommerce platforms, or knowledge bases have enormous content footprints. Navigation in these systems must:

-

Support deep content hierarchies

-

Offer strong filtering and search

-

Allow both exploration and task-specific access

-

Maintain performance and simplicity despite complexity

Design patterns like mega menus, tabbed interfaces, dynamic filters, and progressive disclosure help manage this complexity without overwhelming the user.

Evaluating and Testing Navigation

No navigation system should be considered final without testing. Some effective methods include:

-

Tree Testing: Evaluate how users categorize or locate information in a proposed structure

-

Card Sorting: Understand how users mentally group content

-

Click Testing: Observe how users interact with the navigation before full design is applied

-

A/B Testing: Try different nav labels or hierarchies to compare performance

-

Session Replay Tools: Analyze real-world navigation behavior

Quantitative metrics such as task success rate, time on task, and page depth provide further validation.

Navigation is Strategic Design

Navigation is not a detail to be filled in later—it is strategic design at its most fundamental level. It reflects how a brand organizes information, guides users, and facilitates action. It turns architecture into interface and interface into experience.

Whether you’re designing a startup landing page, a nonprofit platform, or a global enterprise system, navigation will determine whether people stay, engage, and convert. It’s not just about menus—it’s about movement, clarity, and control.

Designing great navigation means thinking like a user, structuring like an architect, labeling like a librarian, and iterating like a product team. It’s one of the most important systems in any user interface—and one of the most impactful investments in user experience.

Our published articles are dedicated to the design and the language of design. VERSIONS®, focuses on elaborating and consolidating information about design as a discipline in various forms. With historical theories, modern tools and available data — we study, analyze, examine and iterate on visual communication language, with a goal to document and contribute to industry advancements and individual innovation. With the available information, you can conclude practical sequences of action that may inspire you to practice design disciplines in current digital and print ecosystems with version-focused methodologies that promote iterative innovations.